Cancer cells often develop tactics to evade the immune system. A research team led by scientists at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center has identified one such mechanism, and it believes targeting it with drugs could potentially improve responses to immuno-oncology treatments.

A protein called ENPP1 that coats cancer cells intercepts warning signals of tumor formation before they can reach immune cells, the researchers explained in a study published in the journal Cancer Discovery.

In mouse models of breast and colorectal cancers, the team showed removing ENPP1 made the tumors more responsive to anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibitors. The over-expression of the protein rendered otherwise treatment-sensitive tumors resistant to the immuno-oncology agents.

When cancer cells divide, chromosomes become unstable with abnormal duplications, mutations or losses. Snippets of DNA from these unstable chromosomes are likely to drift outside of a cell’s nucleus—where they belong—into the cytoplasm. These rogue DNA pieces can be detected by cells and set off an alarm to immune cells, which can then launch an attack.

But why doesn’t this immune signaling always lead to cancer cell death?

“The elephant in the room is that we didn’t really understand how cancer cells were able to survive and thrive in this inflammatory environment,” Samuel Bakhoum, the study’s corresponding author, explained in a statement.

The abnormal DNA pieces are sensed by a molecule called cGAS. It catalyzes the formation of cGAMP, which serves as a warning signal that promotes inflammatory signaling through a downstream pathway called STING.

RELATED: Powering up cancer immunotherapy by improving protein signaling

Previous work by Bakhoum and colleagues showed that cancer cells take advantage of the inflammatory state inside the cells by adopting certain features of immune cells to facilitate their metastasis. The new study set out to explain how cancer cells tackle the warning signals that activate cGAS-STING outside the cells.

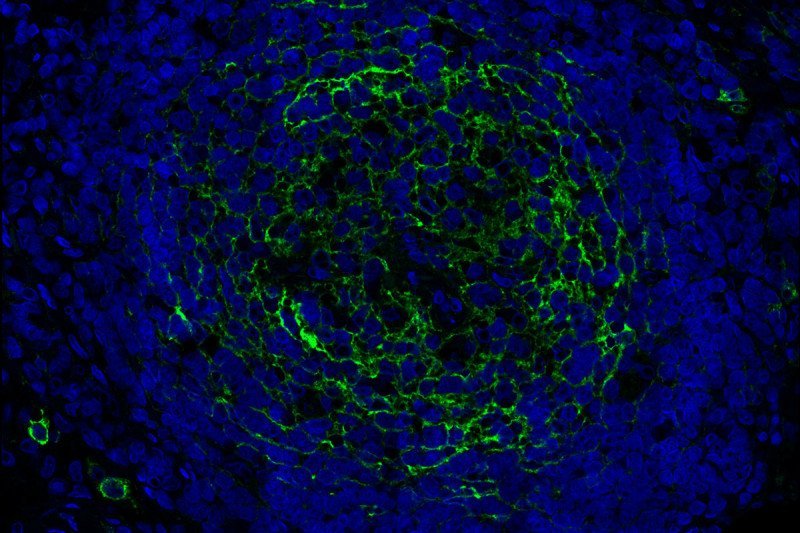

The researchers found that ENPP1 could cut tumor-derived cGAMP that traveled outside the cells, preventing the warning signal from reaching immune cells. That cleaving generated another compound called adenosine, which is known to promote cancer cell migration and immune suppression, the team showed.

So the scientists hypothesized that targeting ENPP1 might improve the response to immune checkpoint blockade. In a mouse model of resistant breast cancer, animals without ENPP1 in their tumors showed slower cancer growth when treated with a combination anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 agents as compared to their unedited counterparts, the team reported. The ENPP1-knockout mice also lived much longer.

The researchers also studied two mouse models with colorectal and breast cancers that were sensitive to checkpoint blockade. They discovered that increased expression of ENPP1 led to resistance to the immunotherapy, as the rodents had more metastasis and reduced survival.

The team then analyzed a large variety of human tumors from the Cancer Genome Atlas. They found high levels of ENPP1 mRNA expression in different cancer types, as well as an association with immune suppression, cancer metastasis and reduced patient survival.

Bakhoum has co-founded a company called Volastra, which will work on translating the research findings into ENPP1-targeting cancer treatments.

RELATED: Enhancing cancer-fighting T cells by manipulating their microenvironment

The Memorial Sloan Kettering-led research marks the latest effort aimed at improving immuno-oncology treatments. Scientists at Mount Sinai School of Medicine recently found that dialing up FAS signaling in tumor cells could power up immune cells to attack cancer. Another Mount Sinai team designed a “nanobiologic” that could train the innate immune system to fight cancer and that improved responses to PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors in mice.

Stingray Therapeutics is working on an ENPP1-targeted candidate SR-8314 from the City of Hope’s Translational Genomics Research Institute. AbbVie, through its acquisition of Mavupharma, also has an ENPP1 inhibitor, MV-626. Other companies such as Novartis are also developing therapies that target parts of the cGAS-STING pathway.

ENPP1’s location on the surface of cancer cells makes blocking it straightforward, and its expression is relatively specific to cancer, the Memorial Sloan Kettering team said. Inhibiting ENPP1 also undercuts cancer in two different ways.

“You’re simultaneously increasing cGAMP levels outside the cancer cells, which activates STING in neighboring immune cells, while you’re also preventing the production of the immune-suppressive adenosine. So, you’re hitting two birds with one stone,” Bakhoum said.